5.1 Validation and comparison of COVID-19 mortality prediction models on multi-source data

Authors: Michał Komorowski, Przemysław Olender, Piotr Sieńko, Konrad Welkier

5.1.1 Abstract

The introduction of a simple decision tree that predict patients’ chances of survival by (Yan et al. 2020a) in the first months of the COVID-19 pandemic laid the foundations for further research in the area of machine learning models to classify COVID-19 patients. Since then a few researchers have validated this decision tree on their datasets and found out that the proposed model is not suitable for patients from other countries than China. It appeared interesting to us and hence in the following paper we present results of our work which aim was to build models on the datasets from China, USA, France, the Netherlands and once again from China as well as on all of them combined in order to find an universal approach for classification of patients from various countries. After testing multiple models such as XGBoost, Logistic Regression, SVM and Tabnet we came up with a conclusion that there is no one model for all of the datasets that is created only from a few most important variables. For all of the approaches these variables included lactate dehydrogenase, lymphocytes and high-sensitivity C-reactive protein collected from the patients’ blood samples. In case of the Chinese data additional variables were age of the patients and their neutrophil.

5.1.2 Introduction

At the end of 2019, the novel coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) pandemic broke out. In the next few months it quickly spread around the world. Daily cases were increasing exponentially. Although most of the cases involved mild symptoms, the healthcare system in many countries still became overloaded. Therefore, the physicians were in an urgent need of a quick system to predict how severe the state of a patient could get, especially if there is a risk of death or a need to be put at the ICU.

A certain solution for this problem was using machine learning to create a mortality prediction model based on easily available biomarkers. One of the first models proposed in may 2020 by Yan et al. (2020a) could predict mortality rates of the patients 10 days in advance with great accuracy. The article is considered the state-of-the-art in the COVID-19 machine learning. Some issues with this model appeared when it was used on data from different hospitals. When used on biomarkers from patients in France, Netherlands and the United States the model’s accuracy significantly dropped.

In our article, we describe how the datasets differ, we analyze how Yan et al. (2020a) model compares to newer model Zheng et al. (2020a) which evaluates hospitalization priority for COVID-19 patients by validating it on different datasets and propose new model which could yield great results on both datasets.

5.1.3 Data description

We have begun our work from analyzing the article (Yan et al. 2020a), authors have created a model based on blood samples collected form 375 patients from the Wuhan region in the first quarter of 2020. Data from another 110 patients were treated as an additional test set. The dataset contains 81 variables, including 74 describing the blood tests results, but not all tests were performed on each patient. Scientists create a model based on three variables: lactate dehydrogenase, lymphocytes and high-sensitivity C-reactive protein, these are going to be crucial also in our work.

The article (Yan et al. 2020a) received several replies, scientists from the USA, France and the Netherlands validated the model on datasets from hospitals from their home countries. The results point to the problem of rashly predicting death for patients who eventually survive Covid-19 infection. They also claim that the Yan et al. (2020a) model learning from most recently performed measurements is not an appropriate tool to prioritize ICU admissions and should therefore use results from first tests.

The datasets from corresponding articles contained 3 previously highlighted features, in the datasets from (Dupuis et al. 2021) and (Barish et al. 2021) there are multiple test results and other useful features such as age, but information about other blood components is not included. The data from (Barish et al. 2021) was especially helpful because of it’s size, it contains informations about 1038 patients.

Table 1: Description of the considered datasets and their dimensions. We highlight, which dataset contains the variables necessery to create model.

| Article | Rows | Variables | Lactate Dehyd. | C-protein | Lymph. | Neutrophil | Age |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| (Yan et al. 2020a) | 485 | 81 | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| (Barish et al. 2021) | 1038 | 14 | Yes | Yes | Yes | No | No |

| (Quanjel, Holten, Gunst-van der Vliet, et al. 2021) | 305 | 15 | Yes | Yes | Yes | No | Yes |

| (Dupuis et al. 2021) | 178 | 43 | Yes | Yes | Yes | No | Yes |

| (Zheng et al. 2020a) | 214 | 33 | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

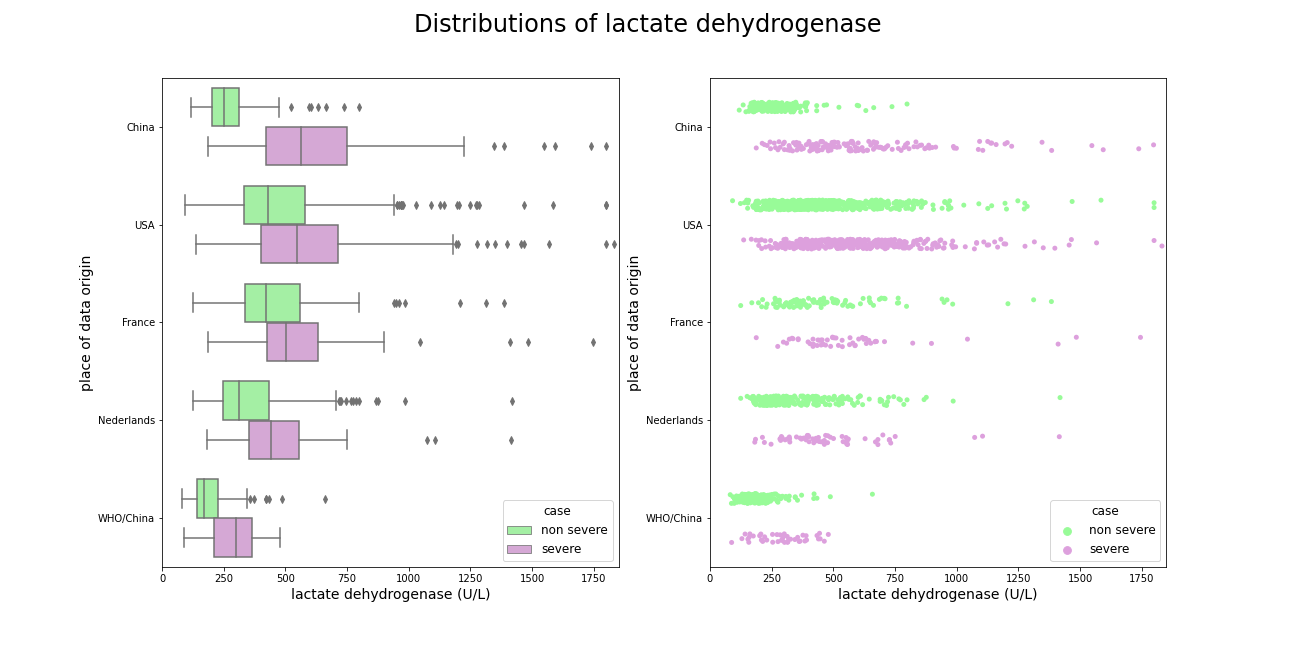

Careful inspection of distributions of these key variables from various articles helps to understand problem with applying model form (Yan et al. 2020a) on dataset from corresponding articles.

Lactate dehydrogenase was the most important feature in model from (Yan et al. 2020a), relying only on its value patients were supposed to be directed to the ICU. The chart shows that indeed distribution of sever cases is significantly shifted towards higer values in comparsion with non severe cases, but such a large difference does not occur in other datasets, patients requiring additional care usually have an increased lactate dehydrogenase, but not as much as patients from China. An interesting dependence ocuurs in the dataset from (Zheng et al. 2020a), a large part of the data also comes from China, there is a great distinction between the severely and slightly ill, but the overall lactate dehydrogenase levels are much lower. Additionally, slightly ill patients from Europe and the US have higher LDH levels than severely ill patients from China.

Figure 5.1: Comparison of lactate dehydrogenase amongst datasets, best separation occurs in patients form China.

A similar situation occurs when it comes to high-sensitivity C-reactive protein, in the dataset from (Yan et al. 2020a) the distributions are clearly shifted among themselves, but similar dependency occurs only in the data from (Zheng et al. 2020a). Patients suffering from the virus slightly and severely from other countries with have less varied level of CRP.

![Comparison of high reactive C protein amongst datasets, again best separations occurs in dataset from [@5-1-yan-et-al].](images/5-1-crpDist.png)

Figure 5.2: Comparison of high reactive C protein amongst datasets, again best separations occurs in dataset from (Yan et al. 2020a).

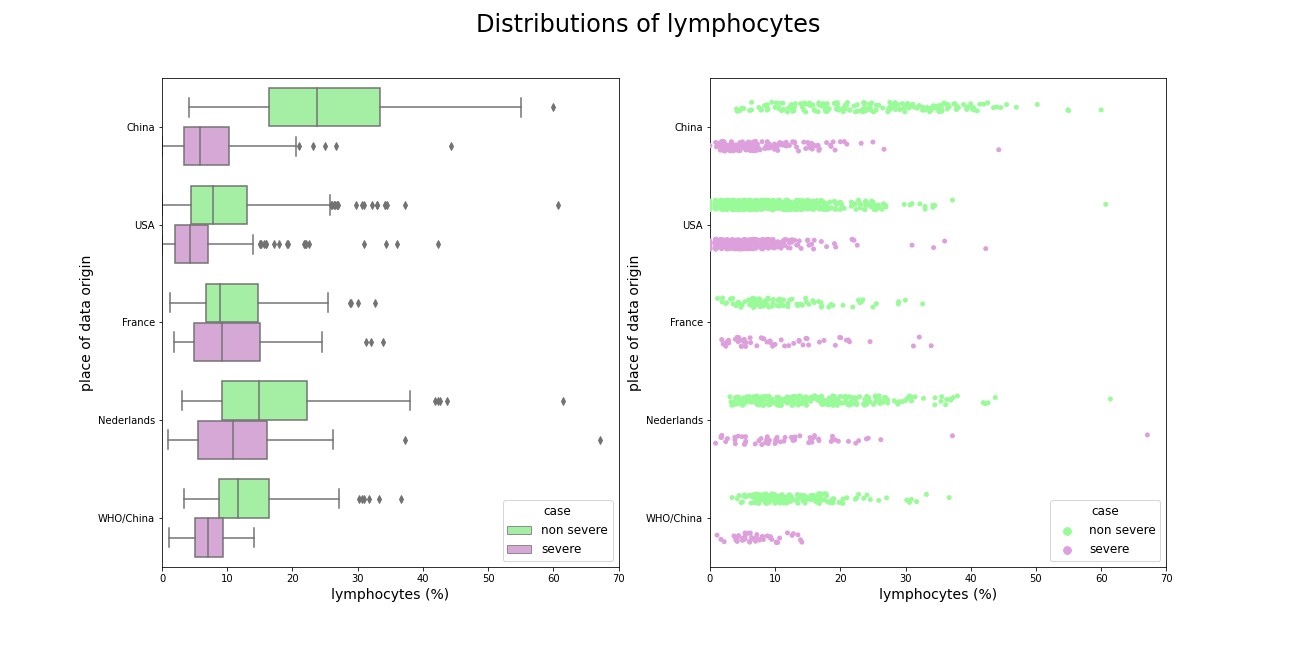

The same dependence occurs with lymphocytes, one additional fact about these distributions is that French do not have lower level of these cells as do patients from rest of the world.

Figure 5.3: Comparison of lymphocytes amongst datasets, slightly ill patients from China has much higher level of these variable than any other patients.

Neutrofil was not used in (Yan et al. 2020a) model, but it separates sever and non-severe cases in both datasets very well.

![Comparison of neutrophil amongst datasets, it was not used in [@5-1-yan-et-al] but it separates sever and non severe cases really well.](images/5-1-neuDist.png)

Figure 5.4: Comparison of neutrophil amongst datasets, it was not used in (Yan et al. 2020a) but it separates sever and non severe cases really well.

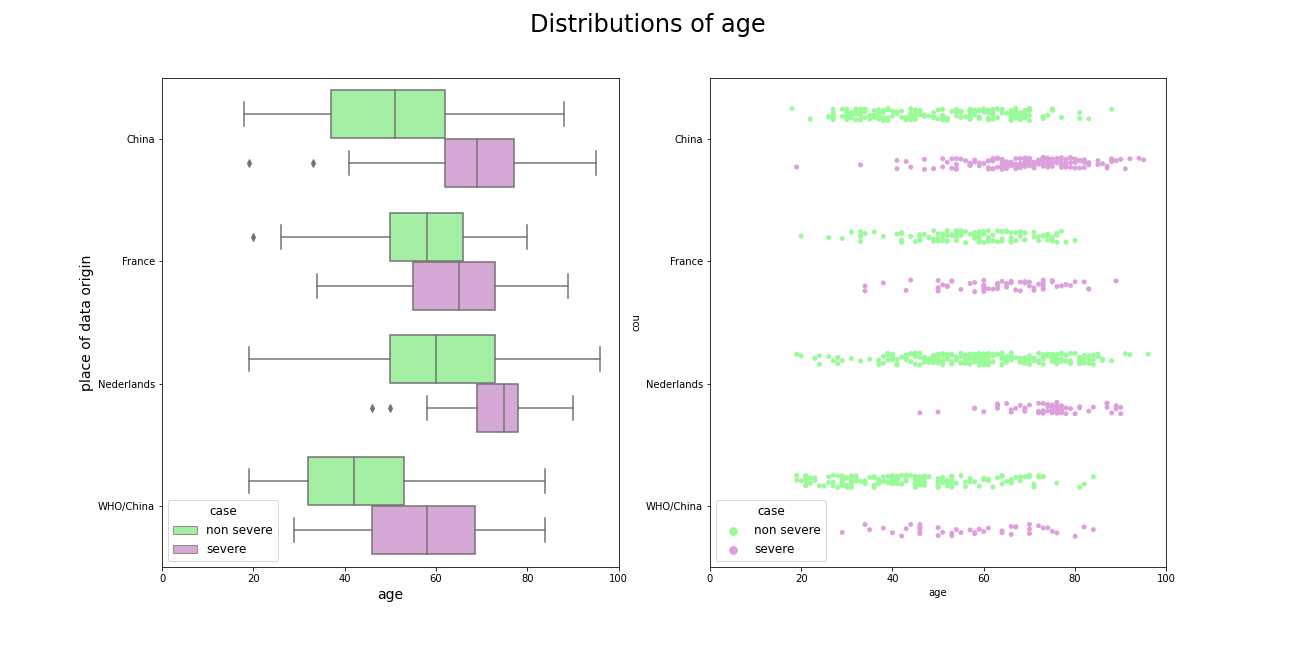

Age is also crucial feature in predicting virus severity, the young people get sick more mildly than the old ones.

Figure 5.5: Comparison of patients age amongst datasets, older people are more likely to experience the virus more severely.

5.1.4 Comparison of the models

We have decided to validate two models proposed by Yan et al. (2020a) and Zheng et al. (2020a). The first one is a decision tree with 3 nodes and the second one is an XGboost model with 4 explanatory variables.

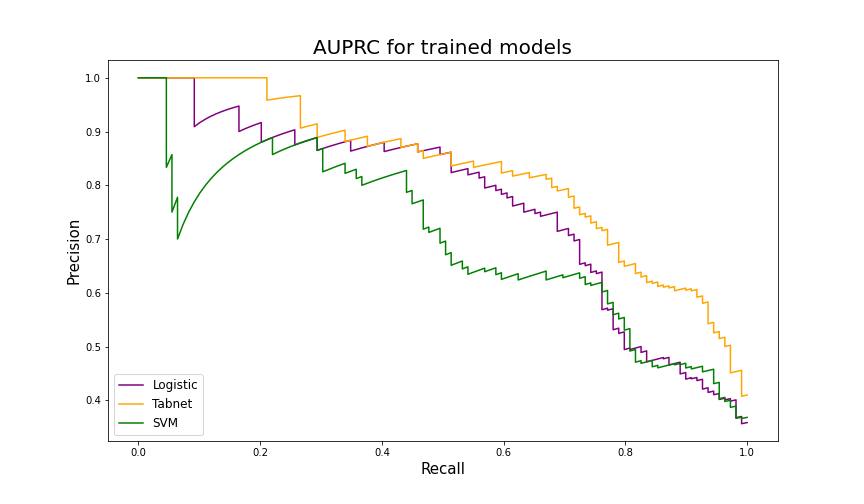

To verify if the model proposed by Yan et al. is effective in predicting COVID-19 mortality amongst patients around the world, validation on external datasets was made. The decision tree was tested on combined data from American(Barish et al. 2021), French(Dupuis et al. 2021) and Chinese(Yan et al. 2020a), (Zheng et al. 2020a) hospitals. The merged dataset has 1842 observations and 3 explanatory variables: lymphocyte, lactate dehydrogenase (denoted by LDH), and C-reactive protein (CRP). All these medical indicators have been previously studied as key factors in severity and mortality prediction(Cao et al. 2020), (Q. Zhao et al. 2020). To compare Yan’s decision tree with exemplary models, we created Logistic Regression and Support Vector Machine (SVM) by using scikit-learn machine learning package (Fabian Pedregosa, Varoquaux, Gramfort, Michel, Thirion, Grisel, Blondel, Prettenhofer, Weiss, Dubourg, Vanderplas, Passos, Cournapeau, Brucher, Perrot, and Duchesnay 2011b). Additionaly we also employed Tabnet, a deep learning model for tabular data (Arik and Pfister 2021). It allows creating high performance and explainable classifier on numeric data. The merged dataset was splitted into a training table (80% of observations) and a test table (20%). Then, newly created models were trained on the training table and validated on the test table. Yan’s algorithm was tested on the same part of a merged dataset as other models. We have selected accuracy, precision, recall, ROC AUC and AUPRC (Sofaer et al. 2019) as final score metrics.

| Model | Accuracy | Recall | Precision | ROC-AUC | AUPRC |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Decision Tree | 0.674 | 0.908 | 0.474 | - | - |

| Logistic Regression | 0.832 | 0.606 | 0.776 | 0.861 | 0.746 |

| Tabnet | 0.840 | 0.569 | 0.838 | 0.913 | 0.824 |

| SVM | 0.777 | 0.596 | 0.631 | 0.843 | 0.699 |

Although the decision tree achieved high recall score (0.908), its precision is unsatisfactory. Models trained on multinational data have distinctly higher accuracy and precision thus they are more suitable for medical triage. Tabnet proved to be the most efficient algorithm, having AUC at 0.91 and AUPRC at 0.824. The SVM was the worst model out of the new ones, with AUC at level 0.843 and AUPRC at 0.699.

Figure 5.6: AUPRC results on the test table from the merged dataset. Tabnet scored significantly better than Logistic Regression and SVM.

Six months after the Yan et al’s paper had been published, another group of Chinese scientists released their article about machine learning models for COVID-19 patients (Zheng et al. 2020a). They examined several algorithms from which XGBoost (Chen and Guestrin 2016a) performed most efficiently. Besides variables that had been used in the previous article, XGBoost proposed by Yichao Zheng et al. also needed information about the level of Neutrophil in each patient’s blood sample. Importantly, this model was originally designed to predict severity therefore it was expected to have high recall and low precision in mortality prediction task.

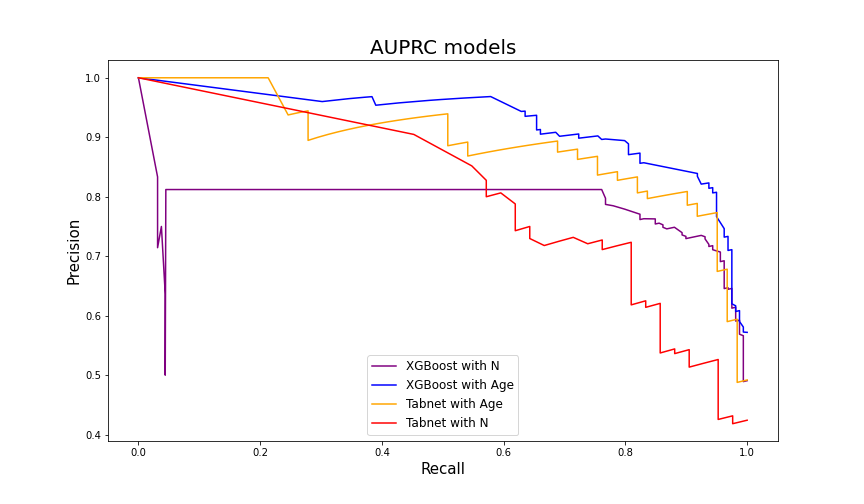

Model validation was performed on the dataset from the Yan et al’s article. To compare XGBoost performance, another Tabnet model was created. It was fitted to the same data as XGBoost and then validated on Yan et al’s dataset. Additionally, we decided to create two versions of each model. The first one with the Neutrophil variable (the same explanatory variables as proposed in the article) and the second one with Age instead of Neutrophil.

| Model | Accuracy | Recall | Precision | ROC-AUC | AUPRC |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| XGBoost with N | 0.573 | 0.994 | 0.515 | 0.865 | 0.791 |

| XGBoost with Age | 0.746 | 0.975 | 0.646 | 0.942 | 0.918 |

| Tabnet with N | 0.538 | 0.976 | 0.432 | 0.868 | 0.787 |

| Tabnet with Age | 0.747 | 0.984 | 0.588 | 0.941 | 0.891 |

As expected, all models achieved very high recall. However, XGBoost from the article (with Neutrophil) had significantly worse performance than XGBoost with Age variable. A similar situation occurred with Tabnet models. Overall, XGBoost with the hyperparameters proposed by Zichao Zheng et al. but trained on data with Age column in the place of Neutrophil had best results with 0.942 AUC and 0.918 AUPRC.

Figure 5.7: AUPRC results on the Yan et al. dataset. Models with Age variable are more effective in mortality prediction.

5.1.5 Conclusion

The first conclusion which we draw from our work is that the original decision tree is not an algorithm that can be universally used to assess chances of survival of any patient around the world. The fact that the blood characteristics vary with ethnic groups is significant and therefore usage of some additional variables can improve the models’ predictive capabilities. This is not what the authors of (Yan et al. 2020a) expected but adding Age or Neutrophil variables to the set indeed boosted the performance. Hence, the intuitive windup would be that the best model is the XGBoost with Age variable since it gets high results according to multiple metrics but it is not that simple. For example its precision is significantly lower in comparison to the Tabnet model prepared on the merged datasets.

Therefore, in the final words of this paper we highlight that none of the proposed models that were validated and compared by us should be used on other datasets than those on which they were trained. The whole process of model preparation for medical use should be performed in each region or at least country or group of countries separately.